|

A Solar Strategy for Africa: International Players Set To Expand Key Markets - PSECC provide mechanism for Solar PV

By Mark Hankins, Africa Solar Designs

04 January 2011 |

Now that real progress has been made in growing global demand and production and lowering costs in developed countries, it is time to

think seriously about kick-starting real solar markets in Africa.

There is a need for a shift in focus on solar markets in Africa away from donor and rural electrification projects to commercial and productive investments.

There is also a need for the international PV industry to aggressively invest in the development of solar markets and not to leave it up to aid and relief organisations.

This must be based on the need to move – today – towards grid-connected and urban markets. As part of this process there is a need to engage and educate

African governments about the current global status of the solar sector and help them build frameworks for industry growth.

Markets for small off-grid systems, those below 100 Wp, are important to kickstart solar industries, but they will be less important in the long term as demand for

them begins to fall.

It is also useful to have an idea of where marketing and development efforts will lead in the long term. 'Off-grid rural solar development' in Africa has dominated

discussion for so long that we seem to have lost the bigger picture. Where does the solar industry want to be in Africa in 10 years? Leaving aside the 'rural

electrification' impact, which is more attractive for a solar company: 20,000 solar home systems at 50 Wp or 500 systems of 2 kW each? Both will result in

1 MW of sales.

Kenya's so-called 'solar PV success story' is a good example of this. Its focus on small systems – to the exclusion of larger commercial or grid-connected systems –

and has resulted in an annual PV market of 1.5 MW that is low-tech, over-the-counter and dominated by small products. But the market is stagnating.

Continued efforts by aid groups to build sales in 'poverty markets' will likely increase the depth and accessibility of small scale lighting systems. However, this will

not build a market with a 20 MW/year solar demand of a scale that is interesting to larger PV supply companies. No matter their importance to the rural poor, LED

lanterns with 1 W modules fall into the realm of the fast moving goods providers from Asia, not solar PV companies.

If healthy markets that are multi-dimensional and sustainable are to develop, solar advocates must prepare the ground for the variety of viable niches that will be part

of a healthy long-term solar market. In addition to village electrification, this includes off-grid markets such as telecoms, tourism, business and pumping as well as

grid-tied and utility-scale markets.

Africa is not solely a poverty market and, in the long term, middle class and commercial groups will do far more to develop solar markets than procurement-driven

public sector projects or the efforts of humanitarian groups.

Every car salesperson knows that, when a customer enters a showroom looking for a luxury car there is probably no need to show the second-hand hatchbacks.

But, in Africa, the solar sales approach shows high-end customers bicycles, not limousines. Africa's most important buyers go for generator sets because they

see generators as being 'classy' and practical solutions - and generator dealers latch on to this. Solar agents do not recognise this market.

The Flawed 'Aid' Approach to African Development

The aid-dominated approach to PV in Africa has led many decision-makers in Africa to believe that solar is about helping poor people. Without detracting from the

hard work of solar NGOs, village solar electrification is relief work and should not be confused as being the foundations of a developing market. If building real markets for solar in Africa, and in doing so reducing carbon emissions, is the objective, NGO contracts to supply a thousand lanterns or government procurements for 100 schools are, at best, stepping stones, but they are not the long-term answer to stimulating wider demand and building solar futures.

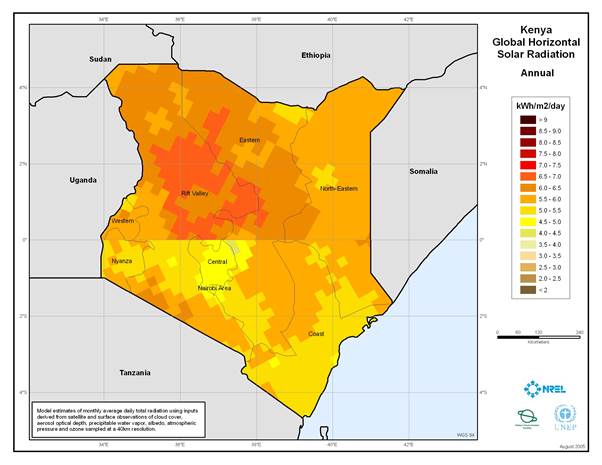

Too many people think of Africa in terms of desperate unempowered off-grid rural poor people with no cash. Aside from a lot of sunshine, the continent's agricultural

sector is growing as are its mineral exports. In some areas, Africa is also seeing massive building projects, along with more frequent traffic jams as automobile sales

increase rapidly, and more and more power shortages as electricity companies struggle to meet spiralling demand. Where there is money – and power shortages -

there is a market for solar power.

The multi-megawatt PV project market is coming to Africa, but not yet. To deliver large-scale projects, a focus on intermediate-sized 50 kW to 200 kW installation

market segments is required.Developers, financiers, solar companies and governments want to push the envelope and open up new markets in Africa. But most are thinking big, and perhaps a

bit too big, for the present undeveloped state of the market. For example, a finance house developing PV project portfolios for African countries, while eager to hear

ideas for innovations in Africa, was unwilling to discuss projects below 1 MW.

On a continent where the largest installed system is 250 kW (Kigali, Rwanda) a 1 MW minimum requirement is unreasonable as a starting target. Even though grid

parity is close in a number of countries, outside of South Africa the type of feed-in tariffs and incentives necessary for megawatt-scale projects are simply not feasible.

Resistance from utility sectors can make agreements problematic and risky for investors whereas smaller-sized projects may be able to fly under the radar and build

up experience as solar is assimilated into power sector planning. When experience is gained on one or two 50 kW projects in a country, these can be bundled by developers into financially attractive packages. But the first step is to gain experience.

There is a need for developers, perhaps with donor agency help, to think bigger than village scale, but a bit smaller than utility scale. Just 10 years ago 50 kW PV projects made industry headlines in Europe.

Grid-Connected Markets

Grid connection is coming in Africa, perhaps faster than expected and definitely in different ways than expected. In the near future, urban PV markets will be as

important as rural markets.

In the mid-1990s, when the annual world production of PV was well below 100 MW, many ridiculed the idea of grid-connected solar anywhere in the world.

Off-grid rural solar electricity made much more sense. How could grid-connected solar prosper when off-grid markets were screaming to be satisfied in developing

countries all over the globe?

In every country in Africa the electricity sectors plan to eventually connect all economically active areas to a national grid system. Arguments and concerns can be

raised about how fast this will occur – or even whether it makes sense – but the fact is that politicians, planners and consumers are united in their desire for grid

electricity. Because virtually all solar in Africa today is off-grid, ministry planners often view solar as a second class option for remote locations where it is likely to

be too expensive to establish a grid connection and where there is little economic activity. It is time for those planning national strategies to look to solar –

and those developing solar marketing plans – to embrace on-grid solar and stop pretending that solar is exclusively for off-grid communities in Africa.

Some say that fragile African grids, with fluctuating voltages and frequent shutdowns, cannot accept PV power but the same thing was said about wind a few

years ago. Now there are multi-megawatt wind projects all over the continent. Surely, the opposite is true - grid connect solar systems can help stabilise grids and,

with small battery banks, can also help consumers weather power outages.

While there are definitely technical, financial and regulatory hurdles to be overcome there are also huge opportunities. From Lagos to Nairobi and from Addis to

Dakar, businesses, hotels, offices and households today buy and install hundreds of thousands of generator sets and battery-inverter systems to hedge against

brownouts. Because electricity can be unreliable in African cities people who require continuous power are willing to pay extra to ensure their supply and therefore

surely it makes sense to use this willingness to pay as a wedge to open new grid-connected PV markets.

Given the choice, a substantial proportion of the middle classes, NGOs and business consumers in Africa would purchase grid-connected systems. Educated

Africans will install solar for the same reasons that people in the North do – because it is clean and silent, reduces carbon footprints, is modern and aesthetically

pleasing.

Net-metering, not feed-in tariffs, will initially be key to developing grid-connected markets, just as they were in Germany and the US.

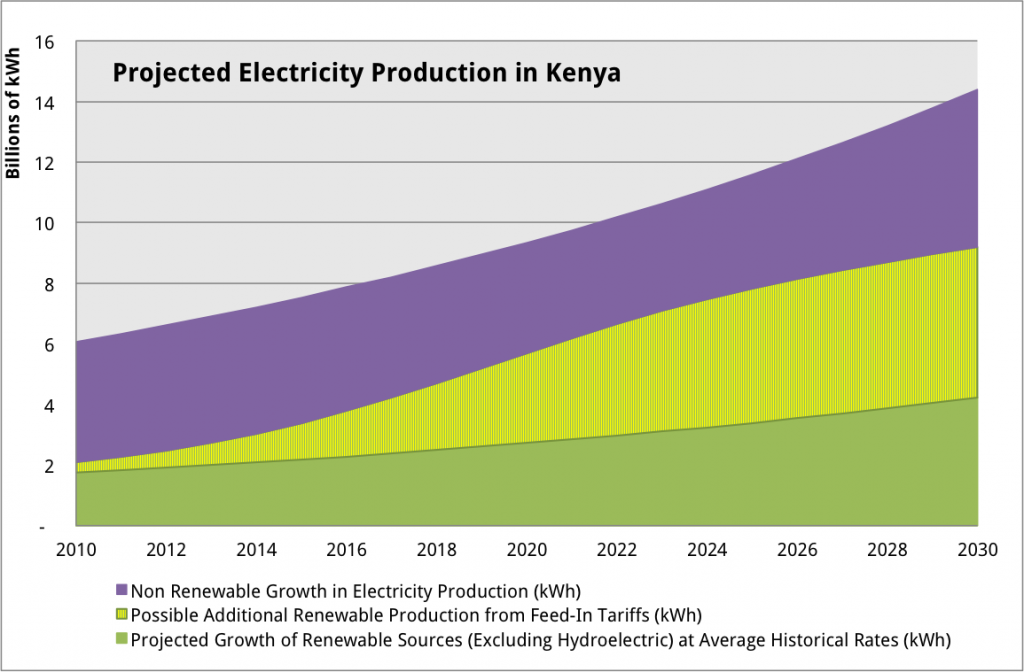

For medium- to large-scale renewables such as wind, hydro and biomass, specialised feed-in tariffs are important policy tools to stimulate investment. Even in

Africa (RSA, Kenya) feed-in tariffs are helping to get renewable power projects off the ground.

However, feed-in tariffs are less suited to PV than other renewable technologies for several reasons. First, there is much less economy of scale in PV; it does

not matter whether a PV installation is 10 kW or 1 MW – the costs are broadly the same. Secondly, because of this scale issue, thousands of dispersed PV

installations make as much sense as a single large plant. But right now PV is still more expensive than wind, hydro or biomass, so it is hard for governments to

justify PV as part of their 'least cost power plan'. However, there is no need to block private consumers who want to invest in Africa's nascent solar market.

Net metering is a low-cost policy tool that allows electric utilities to incentivise on-grid PV investment by private consumers. With it, consumers invest in a PV system.

Instead of storing their PV power in a battery during the day, they store it on the grid by running their meter backwards and selling their output at a retail rate. In the

evenings they draw back the electricity that was generated during daylight hours, with the result that at the end of a month consumers could potentially have a

zero-value bill.

Unlike feed-in tariffs, net metering does not require massive grant support or additional levies on electricity consumers by cash-strapped African governments.

Net metering cannot be unscrupulously 'rigged' because there is no incentive – electricity bills are offset, and no cash changes hands. Net metering also allows

demand to develop naturally. Those who want solar PV and are willing to pay a premium for it will be rewarded. In short, those that want to buy and sell PV power

should be encouraged, not discouraged.

The Benefits of Solar

In Africa the versatility and practicality of solar energy solutions is as important as the cost/kWh.

Too often, electricity is judged on extremely narrow price grounds. Policy-makers, from both government and donor sides, look at the cost/kWh of solar and

automatically disqualify it from discussions in national planning. African energy departments, and the donor agencies that support them, apparently dismiss

solar out of hand because of its high costs. The mentality, it seems, is that Europe should busy itself with developing the PV as Africa cannot afford to do so.

But at the same time, in countries as divergent as Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal and Burkina Faso, petroleum-based generation is sacrosanct when it comes to

investments in power supply. Thermal generation units are purchased to meet 'emergency' peak demands because petroleum flexibly supplies power when it is

needed.

Even though solar PV is an expensive investment it can be an extremely reliable and predictable component source of an overall electricity profile during periods

when electricity is needed.

It is especially valuable during cloudless periods when dams dry up and grid managers must scramble to get thermal units on line, and nothing seems surer than the

fact that as petrol prices will invariably rise the costs of developing and installing relevant and efficient PV solutions will fall.

PV can be deployed in a decentralised manner where it is needed and where space is available. Financing can also be decentralised. The same customers

who buy their own generator and battery back-up sets may consider investing in solar as an alternative to brownouts.

But perhaps most importantly it is necessary to pay the high up-front prices of solar today to build the experiences and capacities that will be needed tomorrow.

Solar did not happen in Germany and California overnight; it took decades of work to get the skills, supply lines, finance and consumer awareness in place.

Governments cannot wave magic wands and make these things happen, at which point solar suddenly becomes 'cost-effective'.

Before achieving 200 MW of installed capacity, a first target of 1 MW has to be reached.

The Role of Industry

Over the past two decades, as solar markets have grown at double digit rates in the North, the job of building up solar markets in Africa has been left to NGOs

aid agencies such as the UN, the World Bank and the Global Environment Facility.

Few African governments have championed PV, and most of the companies that did have offices in Africa have left. This needs to change. As stand alone generator

and petroleum-based power suppliers already know, Africa is a steadily growing market – and a profitable one at that.

Donor agencies have relegated PV to off-grid markets and, moreover, they have left the administration of PV projects to slow-moving government agencies.

Few major solar players want to bid on World Bank-supported government tenders that can take years to develop and which can be expensive.

Thomas Edison and Henry Ford had it right. When they developed their electrical lighting and automobile products, they aggressively took them to the moneyed

classes in large American cities and their companies were successful. With more solar resources than anywhere else in the world, with steadily growing economies,

and with massive shortages of power, the markets in Africa are ripe. But Africa needs solar entrepreneurs that can convince the buyers and it needs the type of

aggressive green investment that took place in the 1990s in Europe.

Solar industries need to work together to build viable markets in Africa and should instead leave the World Bank and the UN to focus on the off-grid poor.

Aid efforts should focus on helping to steer solar policy in the right direction, and tying grant and subsidy support to the achievement of targets. This will require the

active long-term engagement of governments, the private sector, civil society, and the international solar industry.

The global boom in solar – and the accompanying fall in PV prices – has occurred because a handful of countries realised that it would take strong policy initiatives

to get PV markets to a size that would bring solar prices to back down to earth. Bold politicians bet on solar and we are now beginning to see the fruits of those measures.

Because of a lack of disposable income and difficulties, perceived or real, in doing business, Africa has been largely side-stepped in solar energy development

discussions.

Slapping donated modules onto the roofs of rural clinics is an easy way to leave the impression that something is being done in Africa. Of course it is easier to target

support for schools, clinics and village electrification, but until policy frameworks are in place to build sustainable solar energy industries, much international solar aid

support is being wasted on projects in remote locations with no infrastructure and little cash. Sustainable local solar businesses are simply not being created.

As is the case with coal and nuclear industries in the North, there are entrenched interests in many African countries that do not necessarily embrace solar.

Numerous ruling elites manage profitable petroleum and large power project cartels and they could be expected to block decentralised solar and grid-connected

projects. International solar industries and development aid networks that are seeking to build solar markets need to be aware of these interests and find ways to

help civil society empower itself with solar.

As power prices in Africa rise, grid expansion stalls and as grid power availability is constrained, consumers and communities increasingly have to take electricity

production into their own hands. In the long term, this is a good thing, and having a portion of electricity coming from decentralised solar sources is healthy for any grid.

Just as political systems in Africa have evolved to reflect the needs of educated voters, power sectors must change too to allow new segments of the population to

profit from and participate in electricity production. This is the promising future of solar in Africa.

Mark Hankins has worked in the African solar energy sector for 25 years. He manages Africa Solar Designs, a Nairobi-based solar solutions provider that is

currently developing on- and off-grid PV projects. He recently authored 'Stand Alone Solar Electric Systems' published by Earthscan Publishers.

While you were probably having a normal day at work on Thursday 9 February 2012, a small village in Africa experienced its first 24 hours of electricity.

Monte Trigo is a village in Santo Antão, Cape Verde’s westernmost island. The 60-family community is only reachable by boat and is completely dependent

on fishing and its trade with nearby villages. The need of ice, which so many of us take for granted, is a matter of survival for the inhabitants of Monte Trigo.

They need it for preserving the fish, hence the constant and frequent five-hour boat trip (each way) to São Vicente, the nearest main island, for ice purchase.

It is a process far from efficient, wasting precious time that could be used in other activities.

Let there be light

It was to respond to this need that local entities came together to develop an off-grid solar energy project. It was financed under the ACP-EU Energy Facility

programme and lead by local private water company “Aguas de Porta Preta” (APP), in consortium with the local Municipality (“Câmara Municipal de Porto Novo”,

CMPN) and other entities.

The facility installed in Monte Trigo is a Multi-user Solar micro-Grid (MSG) based on a photovoltaic generator, a storage battery, an electricity monitoring, control

and power conversion equipment and an LV distribution grid. The 27.3 kWp PV generator is mounted on a wooden pergola that provides shade to the village’s

schoolyard and therefore added value to the community. Power from the PV power plant is delivered through an 800-metre aerial distribution line to the 60 final

end-users, among them a school, a church, a kindergarten, a health centre, a satellite DVB TV system, three general stores and 22 streetlights.

Challenges and added-value of controlling energy demand

Some of the major challenges of a rural electrification project that uses renewable energy generation are related to the users’ understanding of the technology,

the electricity service, and operation and maintenance activities.

Generally speaking, concepts such as the sustainable and rational use of solar energy, and the implications of the different charging levels of the batteries, are

not easily understood or introduced into the end-users’ daily habits. To address this, the concept of Energy Daily Allowance (EDA) was established in the Monte

Trigo project.

The EDA makes the demand control more intelligent and flexible by introducing the concept that the energy available to each user is caped at an agreed maximum.

This ensures that the plant operates within its rated design and there will be no blackouts or unforeseen increases in operating costs. Also, higher back-up diesel fuel

consumption and components like batteries and inverters operate within their specified range, to increase efficiency and lifetime. This limit is, nevertheless, flexible

according to the plant’s condition and on very sunny days users are encouraged to make use of the surplus generation at no extra cost.

In the initial phase of the project, the designers of the facility system interviewed users to access their energy needs and their willingness to pay the 24-hour service.

This ensured that the community felt involved, as each family chose to contract the EDA monthly fee that better fit them. It also allowed technicians to understand in

detail what would be the best technical solution for the village.

Trama TecnoAmbiental, one of the companies behind this project, has used the EDA concept in other rural electrification projects in different cultures and parts of the

world and it has been well accepted because it responds to users’ needs accurately, guides them through the management of energy use, and also establishes a

fixed monthly energy budget.

The implementation is done through a special type of meter (called an electricity dispenser) that permanently shows the user the available energy allowance and

includes a signal to encourage or refrain consumption, always according to the plant’s condition.

The EDA is a vital design feature, as it is the element from which the PV generator (and then all the other major system components) is sized. So it is essential to

determine in a detailed and accurate way each user’s energy demand. It also estimates any future increase, according to the community’s specific social and

economic environment.

Furthermore, and from a technological stance, the EDA enables components like batteries and inverters to operate within their specified range and so to increase

system efficiency and to lengthen their life duration

A tailored energy service

The Monte Trigo project’s service was set-up using a mixed private/public-utility concept, in which CMPN and APP are directly responsible for the service

management and operation and maintenance (O&M) activities of the facility.

Tariff collection is based on fixed monthly rates related to the EDA and was established within the population’s payment capacity. This not only sustains O&M

but also partially pays back the capital costs.

The O&M activities themselves are organised in order to involve local users and are structured around a concept of three levels of involvement: (1) final users,

(2) fist-level O&M up-keeper/user and (3) second-level O&M technicians.

The first level includes the users themselves, as they are the first component of a successful and durable service. The objective is not only to support them in

maintaining their home installation, but also make their electricity consumption behaviour and habits more efficient.

The second level includes a team of trained users, responsible for the basic daily operation, maintenance and, in case of specific alarm and issues, reporting.

Finally, the operator’s technical personnel are the focal point for problem-solving, ensuring substitution when end-of-life is reached, as well as for specific

maintenance and overall activities.

To ensure the successful implementation of this approach, training and capacity-building sessions where performed by Trama TecnoAmbiental previous to

and during commissioning activities in all three levels. They included theory and practical demonstrations to levels two and three, and also to the project developers’

(APP, CMPN) personnel.

In the same way, the final users where trained to understand the dispenser/meter operation and to follow the good habits needed to use a PV generation-based

electricity service. Practical demonstrations were also performed, directly involving the users, who responded enthusiastically.

Monte Trigans were surprisingly well prepared to accept the basic concepts introduced to them and in a few days started to efficiently manage their energy

allowances.

Importance of strong partnerships

As with any successful rural electrification project, Monte Trigo involved many partners from different parts of the world working together. In isolated communities

such as this one, the quality of the different components of the system gains new importance, so it is essential to involve the right (and experienced) companies for

each job. In this case, the project involved mainly three companies: Trama TecnoAmbiental, ATERSA and Studer Innotec.

From the first days of operation, the local authorities showed their satisfaction with the new 24-hour electricity service, as demonstrated by the visit of the President

of the Republic of Cape Verde (Dr. Jorge Carlos Fonseca) and of the European Union Ambassador in Cape Verde (Mr. Josep Coll) shortly after the project was

commissioned (see pictures 6 and 7).

But most of all, it is the enthusiasm of the Monte Trigo population which demonstrates the success of the project. The villagers’ habits adapted very easily to their new

quality of life and what it brought.

Major changes are already shaping the life of this community: one user already bought his first refrigerator (an A+ energy rating!) and local workers brought in a

welding machine from the nearby village to fix a structure with a defect. It was the first time they were able to use something like this in the village.

It is expected that with the two ice machines capable of up to 500 kg/day production using peak of the day, solar surplus generation will improve the commercial activities on which the village sustains its economy. Mark Hankins has worked in the African solar energy sector for 25 years. He manages Africa Solar Designs, a Nairobi-based solar solutions provider that is currently developing on- and off-grid PV projects. He recently authored 'Stand Alone Solar Electric Systems' published by Earthscan Publishers.

Momodou Keita, town chief of Sanogola, a small village 300km north of Bamako, Mali's capital, stands proudly beside the community's solar-powered

lamp-post – a shiny, blue, enamel-coated construction of welded bicycle parts and water pipes.Ten villages now want these lamps," he announces with pride from inside his traditional Malian mud-walled compound. "Now we have electricity and

it helps us so much," he says, for instance children in the village of Sanogola, Mali, learn to read and write using the solar lamp.

Solar technology is spreading throughout countries across Africa and it is getting cheaper and more efficient. The searing rays of sunlight coupled with the

lack of electricity grids on the continent make this renewable form of energy a no-brainer. But what makes Foroba Yelen, or Collective Light – the name given

to the lamp-posts by the women of the area – so different is that it was designed specifically for the Malian communities who would end up using it, earning funding

from the University of Barcelona for winning a special mention in the City to City Barcelona FAD (El Foment de les Arts i el Disseny/Support for Art and Design)

award, a competition recognising initiatives that transform communities across the world.

Italian architect Matteo Ferroni spent three years studying villages in rural Mali, where close to 90% of the population have no access to electricity. He wanted to

design a light that villagers could manufacture for themselves, so went on to study how welders in nearby Cinzana built donkey carts, the traditional mode of

transport that is still widely used today. He used their expertise, along with parts that could be found in any small village in the country, and came up with a design

that would "work for the people, not the manufacturers". "Wherever we need the lamp to be, we just move it," says Assitan Coulibaly,

the town chief's wife, gesturing to her son who proceeds to rock the lamp-post gently

backwards on to its built-in wheel and trundle it around the yard. "Children can do that. Elders can do that. Everyone can do that," she says with a smile.

And they make money from renting the lamp-posts out to other communities too, adds Keita. "When other villages need light for any occasion theyborrow it and go

for the ceremony and bring it back," he says. "They have to pay to know the value of the lights."

Ferroni noticed how people in rural areas did not follow western night and day sleep patterns. Instead, they wake and sleep depending on circumstances, and it

was often the women who would work through the night using costly and often dangerous paraffin lanterns to finish jobs, such as grinding shea nuts, maize or millet, to sell the following day. "The light is a tool to help women who carry out most of the work in the villages," he says. "If they can do extra work at night, they can bring in more money for the family and in turn improve the education and health of their children."

The lamp-posts have become much more than just

a source of light for the community of Sanogola. They are enhancing their lives economically, socially and educationally,

creating a space for the people of the village to use in whatever way they desire. And 62 more were delivered to communities in the surrounding areas in

December. "This light is the equivalent of the shade of the tree in the daytime," says Ferroni.

Credits:: Tamasin Ford / The Guardian

Rema village in northern Ethiopia, home to the country's largest solar project

By Tsigue Shiferaw

BBC, Rema

Two years after the installation of a solar power project funded by international aid groups, villagers in northern Ethiopia say the sun's energy has turned their lives around.

Rema, 150 miles north of the capital Addis Ababa, is home to Ethiopia's largest solar project.

Here, every house in the village has electricity powered by solar lighting systems.

This is unique in Ethiopia - 80% of the population live in rural areas where only 1% of the population have access to electricity.

Lighting up the countryside has long been a challenge for African governments. Unlike houses in urban areas, villages in rural areas are often difficult to connect to the national electricity grid.

Solar power has been touted by some as the long-term solution to Africa's energy needs.

Domestic solar panels can provide cheap, clean and reliable electricity.

Light for homework

The village roofs are dotted with solar panels. One panel gives them about four lamps. The energy can also be used for radios and tape recorders.

Solar power has had a significant impact on the lives of people living here.

Elfenesh Tefera, 40, enjoys solar energy at home with her 50-year-old farmer husband Aseged Hailemariam.

"Our kids can do their homework at night now, because there is light. They are very happy," says Ms Tefera.

"We've had solar energy for over a year now. We're very happy because we're saving money. Altogether we have eight children, and for our kids at school the solar energy is great."

Her husband adds: "We're taking care of the panels so that we don't have to spend money replacing them."

A local bar has increased its turnover because of solar energy. With lamps running on solar energy, people stay in the bar after darkness falls.

Cold beer is in high demand in Rema - the bar's solar-powered fridge has made it available.

Hirut Kebede, a 25-year old bar worker, says solar panels have changed her life.

"I don't have to struggle with smoke [from the gas lamps] any more. Before we used gas lamps, we had to keep bottles cold by putting them in the sand," she said.

"Now we have more customers and compared to before I sell a lot more than I used to."

Newcomers

Samson Tsegaye, the country director of the Solar Energy Foundation in Ethiopia, says there are currently 300 requests for new solar home systems in Rema.

There are currently 2,100 solar home systems in the village.

Because of its solar power, Rema has become attractive to people from other areas. Paraffin for lamps is often hard to find in rural areas. As a result, newcomers are settling in and building new houses in the village.

A solar technician training school has been set up in Rema where students from technical schools are trained to manage solar energy.

There are currently 33 solar energy technicians who have been trained at the school in Rema, all working in different parts of Ethiopia.

"People are sometimes suspicious of energy coming from the sun," says Mr Tsegaye.

"Some say that it is the devil's work. It was difficult for them to understand at the beginning. But when they have light in their homes, they are really happy.

"They are 24-hour light users, and that is better than the big cities in this country."

Vijay Modi: Shared Solar power grids brings electricity to isolated African villages

The core technology is really just smart metering. You can meter each consumer in real-time every hour. You allow for pre-payment. You can allow for

time-of-day pricing. You can optimize the storage needed for demand and supply management. Ironically, everything we are doing in Shared Solar is

what the developed world wants to do. It is a smart grid with real time measurement and control.

Modi said there were two keys to the success of Shared Solar. Pay-as-you-go amounts as little as 50 cents give poor people flexibility in purchases. And the

metering technology has helped keep costs low. Modi said he’s developing Shared Solar systems for parts of Haiti and other countries. Modi said:

We hope that Shared Solar is one additional tool in the tool kit to bring electricity to the poor and to the 1.4 billion who do not currently have electricity.

Editor’s note: Article kindly provided by Simon Rolland, Secretary General, Alliance for Rural Electrification.]

For additional information:

Alliance for Rural Electrification

An off-grid micro-solar solution to lighting africa

Wednesday, 16 January 2013 12:00:00

created by: Pippa Palmer

Half a billion people in rural Africa live ‘off grid’ with no access to electricity. Yet hand held solar products are proving to be the epicentre of a solar revolution that

will provide power to the millions currently dependent on dangerous, toxic and expensive kerosene lamps. At SolarAid we are driving forward a new sustainable

solar light market in East Africa through our social enterprise SunnyMoney.

Solar energy is nothing new. The first PV-powered satellite was launched in 1958 and solar in industry began to take-off in the 1970s. However, it’s only recently

that this technology has reached the developing world - despite the fact that Africa is one of the sunniest places on earth! The construction of huge energy farms in

the deserts of Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco are examples of how renewable energy supplies are beginning to provide power on scale.

But the biggest energy crisis in Africa is that 85% of the population don’t have access to electricity. The majority of the population live rurally and far from the nearest

electricity pylon, so for these people, solar farms that feed into a national electricity grid are meaningless. As a result, schools, clinics and businesses across the

continent are reliant on kerosene, an expensive fuel that burns, damages health and emits 260 tonnes of carbon dioxide into the air each year. So how do we get

safe, clean, cheap energy to the 70% of the African population that live rurally? At SolarAid we believe that off grid micro-solar products provide the perfect solution.

Micro-solar – or pico-solar - lights are compact all-in-one systems with a battery that can be charged throughout the day and power LED bulbs to provide light at

night. They are portable and range from hand-held products to larger systems that power strip lights and charge mobile phones. But the key is that they are all

off-grid, and offer a turn-key solution – no specialist installation, no specialist knowledge to use. They can be taken home, used in schools, shops, clinics or

whilst on the move. So long as the sun shines by day they are reliable at night, providing power to the millions of people who were previously disadvantaged by

their distance from the national grid.

We’re thrilled to be exhibiting at EcoBuild this year and will be creating our very own dark sensory stand, so that visitors can experience the pitch darkness of a

rural African village at night. To see by smoky kerosene, and then see the brilliant light that comes – for free - from these incredible micro-solar lights! We’ll also

be telling visitors how we’re getting this new technology into the hands of the people who need them most – those living furthest from the grid. With over 250,000

lights sold so far, SunnyMoney is proving the market potential for off grid energy solutions in Africa.

The energy crisis in the world’s sunniest continent causes huge barriers to infrastructural development and the alleviation of poverty. But micro-solar presents an

exciting opportunity to revolutionise the way we think about energy and to realise the potential for renewable solutions in the developing world. We’ve made it our

mission to banish the kerosene lamp from Africa by the end of this decade. To learn more check us out on www.solar-aid.org or follow us on twitter. Or even better

pop over for a chat – and a taste of Africa - at Ecobuild 2013.

tags: energy efficiency ecobuild solar

comments for "An off-grid micro-solar solution to lighting Africa":

Only registered visitors can comment on blog posts.

If you already have an account, please log in or alternatively sign up for this years show

|

![4e8c1fb5eed3b4e26ca54e30e9kenya[1] 4e8c1fb5eed3b4e26ca54e30e9kenya[1]](../assets/images/4e8c1fb5eed3b4e26ca54e30e9kenya_1_.png)

![kenya-map[1] kenya-map[1]](../assets/images/kenya-map_1_.gif)